E ven before the pandemic , researchers long wondered what it would mean if going to work didn’t mean going to work . How might our jobs, offices, and workdays change if modern technology allowed us to disconnect from physical locations? What would be the real benefits? What would be the hindrances? Then COVID-19 hit. From a business perspective, everything became upended and uncertain—but from a researcher perspective, it created a tremendous opportunity. If social scientists ever wanted to engineer a massive study on the effects of an all-digital workforce, this was their chance.

At Microsoft, scientists began considering the research possibilities in early March, a day or so after the directive came down for all employees at their Redmond, Washington headquarters to stay home. Brent Hecht, a director of applied science in Microsoft’s Experiences and Devices division, and Jaime Teevan, chief scientist for Microsoft’s Experiences and Devices, gathered virtually with a half dozen colleagues to consider what had just happened, what was about to happen, and what it all might mean. “One of the strengths of Microsoft,” Hecht says, “is that the people here are really curious.”

Within weeks, the Future of Remote Work Initiative was born. Its members—which today include computer scientists and economists, anthropologists and AI whizzes—began to examine and synthesize studies on the impact of WFH, as well as launch studies of their own. Research ranged from analyses of the importance of ergonomics in home offices (according to one study, 22 percent of employees had no dedicated workspace at home at all) to deep dives into why videoconferences are so draining. Many of the studies broke down into an accounting of losses and gains. Researchers wondered what we had given up in this accelerated rush to remote work, brought on so suddenly and unexpectedly by the pandemic. They also pondered the possible

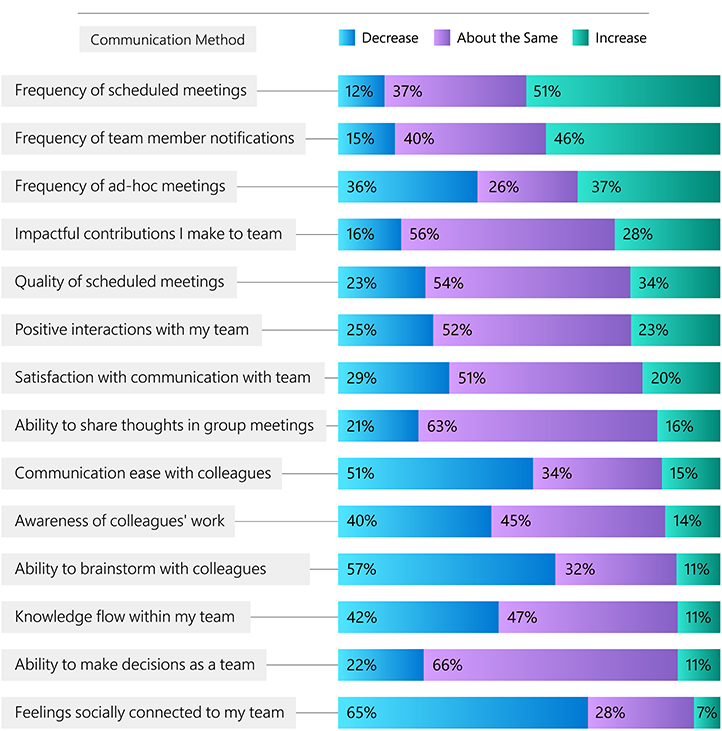

Communication Breakdown

How going all digital, all the time has changed the ways we meet and talk.

Table taken from the study " 'How Was Your Weekend?' Software Development Teams Working From Home During COVID-19"

Infographic by Valerio Pellegrini

gains and how we might keep some of those as we consider a longer-term evolution of work. “ I would say Microsoft views its role in the larger ecosystem of productivity,” says Teevan. “We’re good at getting things done, but it’s also important to think about what we’re helping people get done and how we’re helping them.”

Of course, the tally of losses and gains was hardly clear-cut. A plus for some was a big minus for others. For some jobs, work from home, away from office distractions, had been a blessing; for managers and workers in more collaborative fields, trying to replicate the free-for-all creativity of brainstorming sessions had been brutal. Nearly every positive (no commute!) had its accompanying negative (no binge listening to podcasts as a way to decompress after a long day). Nevertheless, a look at the data so far provides useful insights that can not only help us steer through current challenges, but also inform how we might think about changing things for good once we’re allowed back into our offices.

What We’ve Lost

Social capital Feelings of social isolation have increased during the pandemic, with internal surveys reporting that employees’ needs for “informal contact” and “spontaneous interaction” are not being met in a strictly work-from-home environment. Microsoft’s research found that nearly 60 percent of employees reported feeling less connected than before COVID-19 struck (up to 70 percent in China); 32 percent felt they had fewer opportunities to collaborate. Managers worry that the loss of casual meetups will affect how workers move up company ladders, or don’t. “That’s a classic weak tie situation,” says Hecht. “Weak ties are most famous for job opportunities. Functionally speaking, in an office, you’re able to meet someone in your hallway who could be your future boss.” The research shows the lack of weak ties is also especially treacherous for new employees. “We are seeing onboarding become a major challenge,” says Hecht. For new hires to be successful, managers and fellow employees must be extremely vigilant in checking in and making them part of the culture.

Some companies are finding innovative ways to address this problem. “We have a watercooler bot that runs in Teams, and it introduces you to someone you wouldn’t normally meet,” says Peter Dew, chief digital officer at Netherlands-based DSM, a global nutrition, health, and sustainable-living company. “I’ve been chatting to somebody in Brazil the last few days.” Diara Lo, a community developer and children’s rights activist at Tony’s Chocolonely, uses a less technical approach. “We have these daily check-ins where we see each other between 15 to 20 minutes,” she says. We see each other’s children, houses. It’s really nice. It also gives people more freedom to build their lives the way they want.”

Creative capital Some of the world’s most creative ideas come from spitballing. But the move to remote work has eroded “creative capital,” the energy, innovation, and free flow of ideas that happen when teams assemble in a single collective space to throw out ideas. “Innovation as a team is very difficult remotely,” says Abigail Sellen, a cognitive scientist and deputy director of Microsoft Research Cambridge, who has been studying remote work since the late 1980s. “There’s the stripping away of the energy and the ambience that you get when you’re together. All of that makes it very difficult to do things like brainstorming and idea generation.”

The ever-important whiteboard is getting a WFH makeover, as researchers work on virtual versions. Virtual whiteboards in Teams allows you to collaborate in a shared space and attach images and sticky notes. But this is an ongoing area of intense development—which has already led to things like Together mode in Teams . “Collaboration tools are not just about transactional conversations,” says Microsoft’s Jeff Teper, who oversees Teams. “They are about engagement, about connections, about feelings of belonging.”

Nearly 60 percent of employees reported feeling less connected than before COVID.

Control of our calendar Virtual meetings are hard. And “too many meetings” has become an all-too-common complaint among remote workers, as the cognitive strain of interaction during virtual meetings (Whom do I look at? Is it my turn to talk?) takes its toll. In a survey of 435 workers conducted by Jenna Butler, a senior software engineer at Microsoft, “too many meetings” consistently topped all of the study’s other work challenges, which included everything from workspace issues to distractions from the kids. In fact, 57 percent of workers said their meeting load had increased—a stat echoed by Teams users who are experiencing a 55 percent increase in Teams meetings per week.

In response to the findings of this survey and others, some groups at Microsoft experimented with “No Meeting Fridays” and requests to have meetings begin 10 minutes after the hour, so that workers won’t be staring down the barrel of a three-hour continuous block (research also shows that 50 minutes is about as long as you can expect to hold someone’s productive attention anyway). The survey was a win-win: Workers got the emotional release of venting (always a plus) and fewer meetings. “I’d like to hope that that’s why we do most of our studies, so we could have this sort of impact,” Butler says. “We weren’t going to just say, ‘OK, thanks for sharing all your problems! Back to work!’”

One other practical result: The data has made the company hypervigilant about meeting creep. Already inline suggestions in Outlook make it seamless to protect time for focused work before someone’s calendar fills up. Inline suggestions can also prompt meeting organizers to trim an hour-long meeting down to 45 minutes. Some groups are further making it a practice to ask, “Is this meeting really necessary at all?” and to find ways to go without. “The true measure of collaboration has to take into account the way people and teams actually work, which is both synchronous and asynchronous. Sometimes it’s in virtual meetings, yes. But sometimes it’s in collaborative documents and messages,” says Modern Work VP Jared Spataro. “Often the best ‘meeting’ is the one that didn’t have to happen.”

A normal workday Nine to five? Not anymore. If the transition to WFH has allowed for more flexible schedules, it’s also extended working hours and blurred boundaries between office and home. We can do laundry and watch the kids while we’re working, but then we’re doing laundry and watching the kids while we’re working . Where does work end and fun begin when there’s no office to go to, but you’re always “at work,” sort of? According to one internal study, the workweeks of 7 out of 10 employees had lengthened by at least three hours. In external surveys, work was extending into the weekends more (in some cases, weekend work had tripled), with information workers reporting that it was more difficult to stop working at the end of the day—one Microsoft study showed that messaging traffic in Microsoft Teams between 5 p.m. and midnight had increased by 69 percent.

For many, work is harder when your bed and TV are right there, mere steps away. “If you’re in the office, the boundary between you and your bed can be super helpful,” says Hecht. Experts suggest creating new structures and boundaries to replace the old ones: dressing up for work even when at home, for instance, or taking “micro mental breaks” between stacked meetings. “We’re also thinking about how Outlook defines ‘working hours,’ ” Hecht adds, “and how Outlook might allow users to designate more than one single block.”

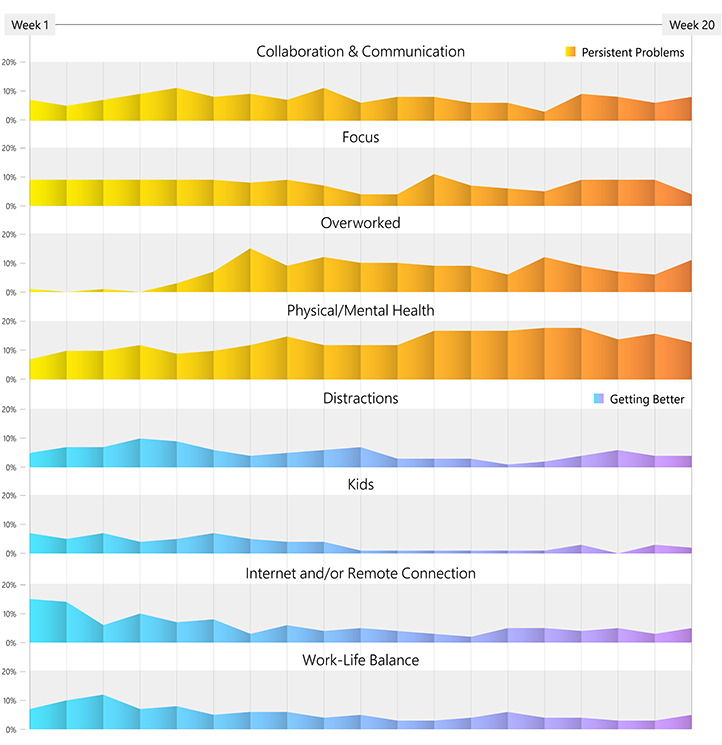

Challenges and Gratitude

Remote work presents many challenges. Some we're getting better at. Some we continue to struggle with.

As soon as workers went remote, Microsoft researchers began conducting nightly surveys with 435 engineers to better understand what they were experiencing. As the weeks went by some things improved (remote connections, kid issues), but others (focus, challenges to physical and mental health) proved to be persistent issues.

Infographic by Valerio Pellegrini

Showing “work devotion” Without the in-person cues that tell their boss they’re working hard—spines bent over desks, not taking lunch—workers are experiencing burnout trying to virtually signal their “work devotion”: working longer hours, sending emails late into the night. “It’s hard to show your dedication when you have less rich communication mediums with your manager,” Hecht says. Solving this problem is tricky, and more analysis needs to be done. One report did find that employees who get more support from management have a better work-life balance and “those with more 1:1 meetings with their managers tend to have seen less of an increase in hours.” This is something for managers to consider, though, of course, managers are overwhelmed, too.

What We’ve Gained

No more commute! Workers, research shows, are not missing those long drives to work and back. In addition to savings in time and gas, we saw blue skies in formerly smog-choked cities for the first time in ages during the pandemic, a plus for all of us. In a study of software engineers by Butler and Microsoft senior research economist Sonia Jaffe, “no commute” ranked high on the list of things people were most grateful for, consistently beating out “exercise,” “focus,” and “mental health.” As with so many WFH benefits, however, there are downsides: in this case, the mental break a commute affords and how that nice long drive serves as both a physical and temporal division between work and home. A full third of workers in one study reported that a lack of separation between work and home was hurting their wellbeing. Experimenting with a bot that helped workers ramp up to and back down from the day, researchers discovered that 61 percent of workers felt they were more productive with the bot, and on average productivity increased between 12 and 15 percent. Microsoft is working on introducing a virtual commute feature in Teams to help workers transition. Perhaps eventually we will be able to keep the best of both worlds.

More time with family (...to a point) The good news: We’re all spending a lot more time with our families. The bad news: We’re all spending a lot more time with our families.

According to internal and external surveys, workers appreciate the extra hours at home. In one study, 75 percent of workers felt that being closer to family improved feelings of wellbeing. But many have also struggled working shoulder to shoulder with their entire clan in the same cramped space.

With an uptick in non-work-related distractions (kids, laundry, TV), workers report the challenge of “carving out time to focus.” But how much of this is a problem with remote work, and how much is it a problem of remote work during a pandemic? Research economist Jaffe stresses the importance of separating the effects

In one study, 75 percent of workers felt being closer to family improved feelings of wellbeing.

of remote work and the pandemic when thinking about the future. Hopefully, in a non-COVID world—when kids can go back to school and spouses can occasionally get out of the house—more time with family and friends will be a distinct positive for remote workers.

Freedom from constant office interruptions Staying focused in the office—surrounded by friendly coworkers who just want a quick chat—isn’t always easy. For many workers, spot interruptions have decreased during WFH. In one survey, 40 percent of Microsoft workers in the U.S. reported fewer work-related distractions during the lockdown, with only 21 percent reporting they had more; in China, it was a 48.5 percent decrease. Perhaps predictably, the increased focus time was dependent on several variables, from the number of people living at home to the sort of work you do (coders seemed to have a better go of things than managers). “People appreciate the ability to focus,” says Hecht. “You don’t have people yelling at you across the hallway. But on the other side of the coin, the initiation of communication is much more expensive.” Expensive, that is, because you can’t just yell a question at a coworker down the hallway.

Flexibility Flexibility has been a major benefit for many Microsoft workers, who have been using their time at home to create their own work schedules, cook better meals, and exercise more (“I was able to walk the dog while I had a build going,” reported one employee).

In one study, “flexibility” consistently held the top spot among things people are most grateful for during the pandemic, even as others struggle with the lack of structure. Microsoft is planning to do further research into the factors that preserve the benefits of flexibility while retaining some of the structure of a more traditional workday. Maybe the midday bike ride is here to stay.

Remote-first thinking Why work from the suburbs when you can be in Joshua Tree? With the shift to WFH, more workers can live wherever they want, even if that means your home is eight time zones away from company headquarters. When everyone’s working remotely, the colleague across the world is just as easy to contact, via email or videoconference, as your office mate. The move to remote has also had an equalizing effect for those who have been working remotely for ages. “There are people who have always been remote: either they have disabilities or maybe it’s just their personal circumstances,” says Sellen. “And many of these people are actually gaining a lot because now, with everyone remote, it’s more of a level playing field, and they have experience and things to teach us.” One study found that 52 percent of traditionally remote workers felt more included now that everyone was in the same virtual room. This will be important to keep going as we return to offices—if we keep some of our remote process active, workers who stay permanently remote will be able to contribute more.

Work is ongoing with the Future of Remote Work Initiative, as its members synthesize data coming from hundreds of researchers (650, at last count) and scores of studies, gaining insights into how to make the office of the future more productive, accessible, and humane. Hecht hopes to look further into the problem of social isolation among remote workers, while Butler wants to do more research into how and why humans are able to pull together during moments of crisis to do extraordinary things. At not even a year old, the Initiative is just getting started, but already the name may need to be reconsidered, as people return to work in various capacities and the hybrid approach gains traction. “Yeah, it probably won’t be called the Future of Remote Work,” says Sellen. “It’ll just be the Future of Work.”